The Maldives is one of the most fascinating archipelagos in the world and there are many reasons to make such a statement. The country is a collection of over 1100 islands and each and every island is different from the other. When you talk about the Maldives, then the first thing that comes to the mind are the clear waters, scenic views, amazing resorts, and even better beaches.

I am a blogger who wants to give the Maldives the exposure that it so rightly deserves. Everything from its beauty to its culture to its people is amazing and that is why I believe that the Maldives is one of the best countries in the whole world.

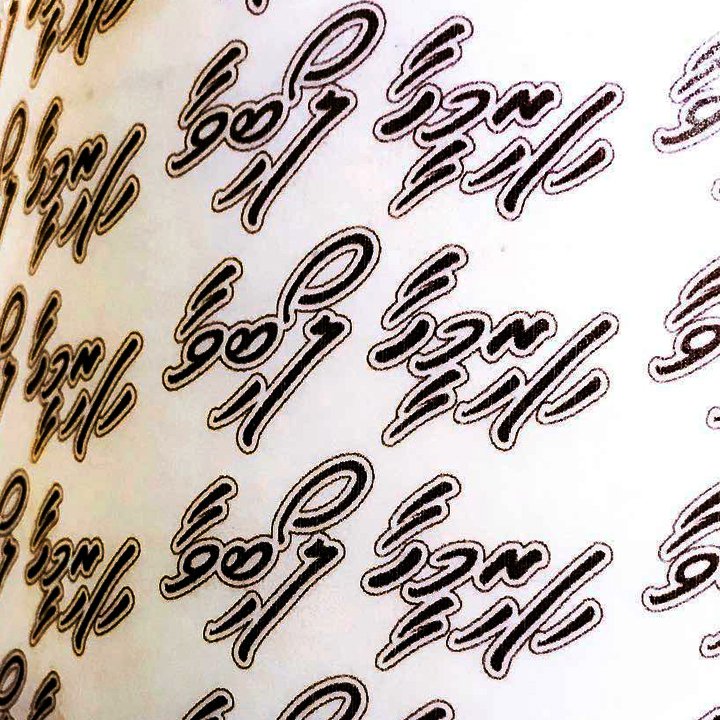

Understanding Thaana

A language is more than a means of communication. It is an expression of unity and nationhood. It gives people their identity and also allows them to identify themselves as part of a family, clan, and country. The Maldives have their own language to boast and have a particularly unique writing system in place to express it on paper as well.

The Maldivian language has its own particular system of writing. The spoken language is written in a system of writing known as Thaana.

Introduction

This personal blog has been created only for the purpose of spreading awareness among people regarding this beautiful nation, its culture, and heritage. We all probably know about the popular narrative that portrays the Maldives as just a vacationing and honeymooning spot. However, there is definitely much more to the people and the country than just leisure trips for foreigners.

The Maldivian population has an extensive culture even though they are just above four hundred thousand in number.

Recent Articles

Osama Bin Laden And The Maldives

The title can be a little misleading however, the Maldives has no affiliations with Osama bin Laden whatsoever. However, two Maldivian journalists belonging to the Huvaas Magazine went on to get some information regarding him and came across, now veteran Pakistani journalist, Hamid Mir who happened to have gotten the opportunity to interview the world’s most wanted person at the time.

Sis Loves Me is the adults-only series featuring the world’s craziest step sisters living up their fantasies about intercourse with step brothers. Established in 2016 it continues with updates and the database is already over 200 episodes long. See yoruself!

Property Sex is the way of doing business, the American way. Watch female realtors doing their best to sell the property. And they are basically bending over to please clients. Sealing the deal is the goal.

Girls Only Porn is the place to visit for all your needs in field of girls only fun. Watch them engage with no boys allowed nearby. Production of Nubile Films crew.

BBCPie.org is a totally new series dedicated to interracial creampies in 4K HD. It features the world’s most-known stars and some very hung black guys doing it right in front of you.

Transsensual is your #1 choice if you are curious about discovering your turn on for transgender models. Watch them engage in all gender fun in those fantasy real life situations!

Mommy’s Boy is a long-awaited debut of 2021. If you are familiar with Mommy’s Girl series then you will be right at home with this series. Boys becoming men thanks to moms and their experience.

MyPervyFamily has yet to find taboo step family configuration that’s not gonna make the cut. Watch the hottest affairs of single family members in this exclusive!

Boy For Sale is the unique experience of fictional marketplace for slave boys. They want to become the object of desire for wealthy men and it happens right after they are auctioned by the secret dominative society.

Filthy Family is the content you’ve been seeking if step family fun on the kinkiest level is your thing. Watch Bang Bros approach to the genre – featuring nothing but the finest storylines, the hottest actors and the filthiest minds. It just can’t go wrong!

LezCuties is the European way of having girl on girl love. Watch the most beautiful teens engage in 100% lesbian scenarios. Discovering their sexuality and having lots of fun.

Blacks on Boys where guys just want to have some fun. Watch the most intense interracial meetups where curious gay males are ending up having some of the kinkiest fun possible.

Follow Us

OUR SOCIAL MEDIA CHANNELS

Warning: strpos() expects parameter 1 to be string, array given in /var/home/internet/maldivesculture.com/wp-includes/compat.php on line 441

Warning: strpos() expects parameter 1 to be string, array given in /var/home/internet/maldivesculture.com/wp-includes/compat.php on line 441

Warning: preg_match() expects parameter 2 to be string, array given in /var/home/internet/maldivesculture.com/wp-includes/class-wp-block-parser.php on line 261

Warning: strlen() expects parameter 1 to be string, array given in /var/home/internet/maldivesculture.com/wp-includes/class-wp-block-parser.php on line 333

Follow us on social media to keep up-to-date with latest news, discounts and events.